Writing

There are two kinds of successful papers, (1) great work with great writing, and (2) okay work with great writing. Unfortunately, writing is generally accepted as a form of art, which holds science back as good artists are rare. In this guide, I present paper writing as an engineering problem that you can solve by applying known techniques to consistently produce good papers. Using this approach helps me write clear papers, with reviews such as “with respect to clarity of thought and execution, this is the best paper I have read in a while”.

Each section starts on a new page, and each figure is cleanly positioned within each page.

Each section starts on a new page, and each figure is cleanly positioned within each page.

Planning, design, and structure

The first task is planning, as having a clear model of what you are doing helps you minimize unnecessary work and write more clearly. That’s “and”, not “then”, since writing and refining your story is a continuous part of the overall process rather than something you do at the end. As part of your story, you must find a good figure that explains what you’re doing for your first page, which is more convincing than any textual introduction. The overall structure is also worth spending time on, since spending time dividing sections properly pays off when writing and refining each section.

Use a formulaic structure, starting with a four-sentence abstract and an introduction that summarizes each section. Then present the problem statement including any necessary background and no more, followed by your contributions. Describe your results and your limitations as precisely as you can, then discuss them in a more relaxed tone. Unfortunately, you may need explicit “related work” and “conclusion” sections to please reviewers expecting them.

Planning research

Do not throw yourself into a project without a plan or you will waste months on work that turns out to be useless.

Before you think about writing, plan what research to do and how. Form a mental model of the problem space by reading related work, even if you initially think some of it is not related enough. You may change your plan at any time, but you must have a plan at all times, including concrete research questions and requiring at most one miracle. Any hypotheses you make must be falsifiable, and you should pre-register them using a service such as the Center for Open Science.

Make sure that you have a model of how things currently are and what your contributions are. One useful kind of contribution is to show that previous assumptions do not hold, though you must be careful to say people were wrong, not stupid. If you achieve your end goal, your work should have a clear impact, otherwise nobody will care about any individual paper towards that goal. There is no point in doing research just to address “gaps” in human knowledge, as there are infinitely many gaps, thus the finite amount of work you can do addresses zero percent of them.

Before you start, answer the Heilmeier Catechism and question the scope of your project. Stay on the Pareto frontier of risk vs reward, as it’s always possible to make a project more complex, but the increase in reward may not be worth the increase in risk. Any concrete artifact that you create, such as a software system, should be as small as needed to make the theoretical point you want to make. Do not spend a year on engineering to save a month on storytelling.

Writing continuously

Your workflow should be to write, do research, get feedback, and repeat as many times as possible.

Writing is a part of doing research, not a separate activity after the fact. Writing helps you decide what work lies ahead and avoid unnecessary work that does not belong to your story. The only way to find a good story with a pedagogical running example is to iterate over and over, thus you must start early. You must present a clear goal, such as influencing policy or encouraging specific research avenues, a pile of technical results is not enough.

Use your limited time to design your story and to do research, not to micro-optimize your text. Focus on how you can change your readers’ ideas, which is what they find valuable. Most readers of a scientific paper are looking for an excuse to declare your paper boring and stop reading it, which they will do if the story is boring regardless of how neat individual phrases are. Micro-optimizations reach diminishing returns very quickly, so do not get stuck on polishing individual sentences or worrying whether your great-grandchildren will find your paper perfect.

The most useful tool to improve your writing is feedback, which you need early and often to validate that your story makes sense. This is similar to how engineers need frequent user feedback to ensure they are building the right product. You thus must have a short draft of the entire story early, even if it is mostly a brain dump, without worrying about formatting requirements or precise technical details. Your early drafts will not have real results, so write about the results you think you can realistically get.

Designing figures

“A picture is worth a thousand words” is not just a cute saying.

Figures are as important as structure for reading comprehension, including tables, algorithms, and code snippets. You should include a figure in the introduction, ideally on the first page, that succinctly describes the problem and your contribution. You can convince your readers with a good figure better than with any written introduction.

Hold figures to the same standards of scientific rigor and clarity as written words. Tell exactly one story per figure, make them self-contained, and minimize the length of captions. Do not sacrifice validity for aesthetics, so start your graph axes at 0, only include trend lines for continuous measurements, and include all data even if some of it goes against your story.

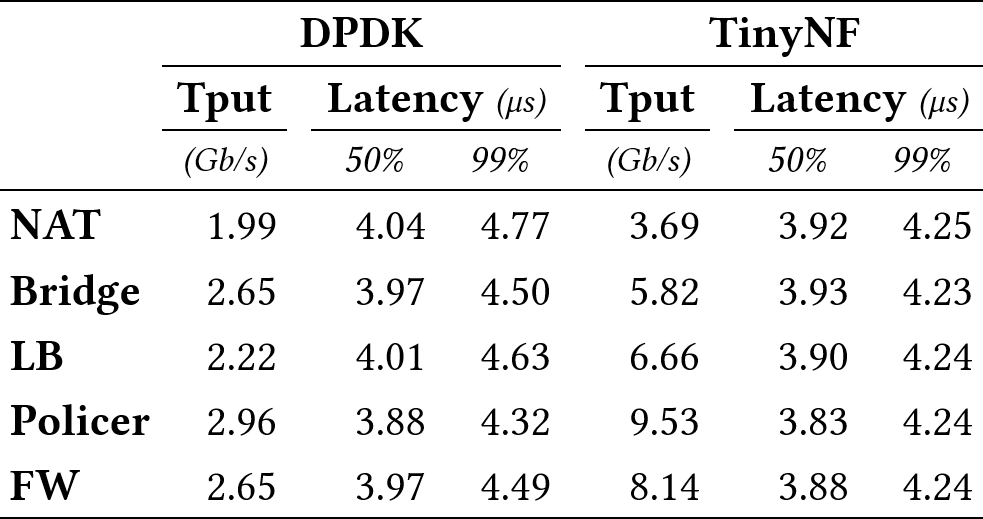

Make your figures as clean and minimal as possible, especially tables, to enable readers to focus on the data and the story you are telling. Omit vertical lines in tables and only include horizontal lines above the first row, below the header row, and after the last row. If a table has multiple header levels, such as when comparing multiple measurements for multiple scenarios, add partial horizontal lines between the first and second level rows.

A clean table with multiple header levels.

A clean table with multiple header levels.

Designing the structure

Spend time on your structure and story to save time writing and rewriting individual sections.

Good structure enables readers and writers to focus on one section at a time without the need to keep the entire paper in mind. Start with an introduction that summarizes each section and initially doubles as a paper prototype, then a problem statement that includes necessary background, then your contribution, results, limitations, and finally a discussion. Find a good running example you can use throughout the paper, possibly in different variations to illustrate different points, and do not use any other examples. The messy process you followed to obtain your results, or the exact way you split writing tasks among coauthors, does not matter to readers and thus must not influence structure.

Use an integral number of pages or columns per section, planned at the beginning and only changed if really necessary, including space for figures. Just as page limits for papers force you to write concise papers, limits for sections force you to write concise sections. This also ensures you never have to decide which section to cut to make the paper fit its overall page limit, since the paper fits if all sections fit. Feedback is also easier to give and to apply this way, with less risk of wasted feedback on content that ends up being cut, since the overall length of each section is unlikely to change.

Start each section with a summary, then write self-contained groups of paragraphs that each start with bolded words giving away the conclusion of the paragraphs. There is almost never a need for numbered sub-sections, as these are a sign the section should be split into multiple sections. You may refer to past paragraphs if needed, but not to ones the reader has not read yet, except in the paper’s introduction. Try hard to only refer to figures in the page they appear, as otherwise your text is no longer self-contained.

Writing the abstract

Most potential readers decide to continue based on your abstract, thankfully there’s a formula you can use.

You only need four sentences in your abstract, namely (1) what the problem is, (2) why it is a problem, (3) what your idea is, and (4) what results from applying your idea. The problem must be a real problem, such as large losses of resources, injury, or even death. Do not use problems of the form “researchers aren’t happy” or “nobody has studied this idea in the context of that theory”, these are not real problems, but they may cause the real problem you should talk about.

Your abstract should be widely understandable since people reading it may not be in your subfield and definitely haven’t read the rest of the paper in which you define specific terms. Mind your vocabulary and your assumptions and get feedback from someone not in your usual collaborators. The choice of reviewers for your paper is also typically influenced by your abstract, so make sure you don’t accidentally imply your paper is in a different field than you think it is.

Writing the introduction

Make your reader want to read the rest of your paper by presenting its contents in a punchy introduction.

The introduction summarizes each section in one paragraph in the style of an impartial news report, ending with a forward reference to that section. Sometimes multiple related sections can be summarized in a single paragraph, such as multiple sections that test different hypotheses about the proposed solution. This obviates the need for a “roadmap” of the form “In the rest of this paper…” that is found in so many papers despite being a boring waste of space.

The first few sentences of the introduction should be a strong statement of the central contribution to clearly position the paper. Give away the “punchline” of your paper immediately since a paper is not a thriller, people read because they want to know the details. Do not begin with philosophical platitudes or dictionary-style definitions. You can often make your introduction punchier by cutting the first sentence you write.

The introduction ends with a list of the paper’s contributions, in terms that must be clear to readers without reading the rest of the paper. You set the bar for your paper with the list of contributions, thus you must be honest and clear in it. If you do not meet the bar you set, readers and especially reviewers will be disappointed, no matter how good the work is.

Stating the problem

Before any talk of contributions, explain what goal you’re working toward.

After the introduction, use a section to define the problem without mentioning your contributions. In the style of a textbook chapter, introduce the subfield and the problem, explaining the achievements of previous work, new and old. By the end of the section, the reader should have a good intuition of what contributions the paper will make, even though those are not stated in this section. For instance, you may emphasize a specific limitation in all previous work, which will make the reader want to continue reading to see how you address it.

This section should contain exactly the background the reader is not expected to know, no more and no less. As Leslie Lamport explains, “state the problem before describing the solution”. For instance, a computer science paper does not need to explain that computers have a CPU but may need to explain recent trends in computer networking hardware, leading readers to notice a gap in current hardware models. Stating the problem may be particularly long for papers that require deeply technical knowledge few readers have.

This section must not act as a wall between the reader and the rest of the paper as it is a “problem statement”, not a “general background”. Do not present every single achievement of every single piece of work in the area. Instead, summarize work relevant to the problem at a high level, in terms of advances, limits, and tradeoffs. Convince knowledgeable readers that you have done your homework, i.e., that you are aware of the contributions and limitations of new and old work on the same problem.

Describing the contributions

Explain what you bring to the table and why it’s as simple as possible.

The contributions are typically split into design and implementation, but there can be more sections if it makes the story clearer, such as introducing one main idea then multiple consequences. These sections should look like textbook chapters describing the reasoning behind the contributions along with enough details to enable a knowledgeable and resourceful reader to redo the work themselves. This includes concise descriptions of the inputs and outputs of each process, along with entire algorithms if needed, ensuring that readers do not need to combine scattered pieces of information on their own. Ideally, your contributions should be based on principles applicable beyond your paper to a wider domain, which you should highlight.

If possible, show how your contributions simplify the world, since adding complexity has a very high bar for acceptance. Avoid writing about various techniques you propose one by one without any overarching plot, since a mishmash of small improvements is rarely interesting unless the result is truly exceptional. Storytelling is particularly important here, as you can turn “a set of related contributions centered around a key insight” into “a bag of unrelated tricks” with a bad story.

Explain why you cannot achieve the same results in a simpler fashion, or if you can, do it and then come back to writing. One way to do so is to start with the simplest possible technique, progressively showing that it cannot work, and refine it. However, state upfront if a technique you present is not your actual contribution, and only do so if understanding such a simpler technique is useful to understand the rest of the paper. Do not argue that your work is good or simple because you intended it to be so, remember that red pandas intend to scare predators when standing up but they just look adorable.

The red panda’s stance is designed to scare its opponent! It’s not very effective…

The red panda’s stance is designed to scare its opponent! It’s not very effective…

Describing the results

Meet the bar you set for yourself in your introduction but keep your story in mind and never lie nor exaggerate.

Present your results in a precise and thorough fashion, in one section per category of experiments. Begin each such section with a description of the exact experimental setup, with enough detail that someone else could reproduce it. The results should be described in the style of a lab report, impartially describing the results and clearly stating which parts are conjectures about the results.

How you present results is a part of the story, do not write a lab notebook with everything that happened in the order it happened. Order experiments by importance of their results, whether positive or negative. Explain any unusual results, and any missing results if you could not run some experiments that a reasonable reader would expect. If your contributions or experiments changed after your first batch of experiments, such as adding more specific experiments to understand a phenomenon in more detail, you should describe such changes, as Andreas Zeller points out.

The validity of your results is the most important aspect, much more than whether they support any hypotheses you have, so don’t exclude poor results or inconclusive experiments. Each experiment must be able to disprove something, an experiment whose results could be explained regardless of the ground truth is pointless. Focus on high-level takeaways such as two techniques having equivalent performance, not on specific numbers that would change with small experimental changes such as one technique being 0.42% slower on one benchmark. If you have more than one contribution, you must perform “ablation” studies in which you measure the effect of each contribution, otherwise some contributions may turn out to be useless as evidenced by Rizzi, Elbaum and Dwyer.

Describing the limitations

Your contributions cannot be perfect, and your experiments cannot be exhaustive, so explain your limitations.

Describe what you haven’t done and what problems your experiments may have in a dedicated section, to maintain scientific rigor. This section is stronger if your hypotheses are stronger, since strong hypotheses are less likely to be right for the wrong reasons. As Richard Feynman once said, “you cannot prove a vague theory wrong”. Similarly, your limitations will be less damning if your experiments have many possible outcomes, since in the extreme case a single yes/no answer could be right for many wrong reasons.

List the main threats to the validity of your work, at least internal, construct, and external validity, though you could do more. Internal validity is whether the effect you measured is linked to the cause you intended to vary. For instance, if you try to correlate patient outcomes after the fact to the kind of medicine they were prescribed, this link is threatened by sicker patients being prescribed stronger medicine, making sickness level a hidden variable. Construct validity is whether the low-level metrics you measured are representative of the high-level constructs you intended to measure. For instance, when measuring treatment effectiveness, the link between health measurements and the construct of medicine effectiveness is threatened by the placebo effect. External validity is whether the findings are generalizable to other contexts, which is naturally in conflict with internal validity since more controlled experiments have clearer correlation links but weaker generalizability. For instance, if patients’ diet was heavily controlled while they were under a treatment, external validity is threatened by whether that diet corresponds to what an average patient might eat.

Do not weasel out of important limitations, neither by drowning them in a sea of minor limitations nor through weak or unfalsifiable counterarguments. Nobody expects your experiments to be free of limitations, and everybody understands that there are many small limitations everywhere, so list all main limitations and only those. It’s better to admit that you have no strong counter than to make unfalsifiable or circular claims such as defending the lack of evidence for a theory using an explanation based on that very theory. Your assumptions do not have to be tested, but they have to be testable.

Ending the paper

While a discussion is all you need to finish, reviewers may have expectations you need to satisfy.

Discuss your results in a separate section, more relaxed in tone than the rest of the paper, since at this point you have earned the credibility necessary for your opinion to be interesting. You can include commentary about related or more general areas and problems. Aim to be useful to readers by describing what you think are interesting next steps, how your perception changed as a result of the work you did, and which leads you think are dead ends. Do not promise specific future work, as you are unlikely to keep such a promise due to the nature of research, so all you would do is discourage readers from trying to do it themselves.

You may want an explicit “related work” section to please reviewers, even though such a section makes little sense since if the work was related you should have cited it already. This section should be a sequence of disjoint paragraphs, each focused on work related to one aspect of your problem or context. The only goal of this section is to show reviewers that you went above and beyond in finding related work. Do not bother finding a story to tell, there is no need for one and it is unlikely you could find one anyway.

You may also want an explicit “conclusion” section to please reviewers, even though it is not necessary either as all key results should be in the abstract and introduction already. Some reviewers expect papers to finish with a conclusion that more or less resembles the abstract but with more detailed results, less background, and in the past tense. However, if you do not have the space, you can skip the conclusion, as even reviewers who care usually find it less important than related work.

Linking your paper and data

Don’t be a part of any reproducibility crisis, make your paper as easy to reproduce as possible.

Maximize the reproducibility of your work by publishing your data, including the instructions and code necessary to run your experiments and plot their results. You will have more impact if you enable others to easily build on top of your own work than if you isolate yourself. Do not worry about someone else using your data to scoop your next piece of work, as you have quite the time advantage since your paper and data become public at least months after the original submission. Do not worry about someone finding a potential mistake either, as the peer reviewers and editors handling your paper are just as responsible for your paper’s correctness as long as you behave honestly.

A small “data availability” section right before the references is enough to let readers know where they can get your data and what to expect. Alternatively, a short sentence at the end of your abstract with a link also works, as long as the link is to a permanent archive and the data includes its own documentation. Do not require people to email or otherwise contact you for the data, and especially do not use vague terms such as “upon reasonable request”. If you absolutely must comply with an externally-mandated process for data availability, be transparent, since shenanigans are a bad look.

Sentences, verbs, and terms

The same techniques for high-level structuring are useful for low-level writing. By limiting your options, you will consistently produce better writing even if the theoretical best is no longer achievable. Sentences, verbs, and nouns should all be simple and precise, without regard for artistic concerns such as avoiding repetition. Getting feedback is important, but you can go surprisingly far with your own feedback using a few techniques.

Sentences

Keep your sentences basic and avoid constructions that encourage long or useless sentences.

Write simple sentences that make one point each, without fancy constructions nor artistic variations in structure. If you have multiple points to make, write multiple sentences rather than connecting them with linking words. If your points are related, state them using sentences with the same structure. Explain the reasoning behind decisions before the decisions themselves, especially if you can preempt reasonable reader objections, to help readers maintain an uninterrupted stream of thought.

Omit optional text, since your paper’s length is likely limited, and your readers’ attention span definitely is. Do not write text in parentheses, nor within em dashes, nor in footnotes, all of which indicate optionality. Either such text is important enough that it should not be marked as optional, or it should be cut. If you believe entire sections are optional but still interesting for a subset of readers, put them in an appendix or a self-published extended version.

Do not use colons nor semicolons as they lead to runaway sentences which are best split in two. The one exception is using semicolons to separate inline lists, such as when listing (1) your first contribution; (2) your second contribution; and (3) so on. Inline lists are more compact than bullet lists and only look odd for lists that are anyway too long, so use them always.

Verbs

Verbs are the workhorses of sentences, so using precise verbs with simple tenses is key.

Use precise and short verbs, not complex of overly general ones. The canonical example of a shorter verb is “use”, which is always better than “utilize”. A precise verb such as “estimate” reads better than “obtain an estimate of”, which is such a general verb you need to add nouns to clarify it.

Use the most precise subject possible for all verbs, since abusing “we” muddles writing. “We” refers to the authors directly doing something, though it can also include the reader, as in “we will see later”. Do not give agency to inanimate subjects such as claiming a figure “shows” something but remember that automated systems are animate and must be used as subjects even if you created them. Only use the passive form when the object is more important than the subject, and only omit the subject when it truly does not matter.

Use the present tense outside of references to other paper sections, in which case the past and future are appropriate. Do not use other tenses. Use continuous and simple tenses consistently, which mostly means keeping to simple tenses.

Words

Individual words matter, and conveniently what’s best for your readers is also easiest for you.

Use precise words to state exactly what you want and not something different. Understand the differences between pairs such as “complex”/”complicated” and “enable”/”allow”, as these are not synonyms and have their specific uses. Do not use vague qualifiers such as “very”, “much”, or “somewhat”, known as weasel words. If you use bracketed references, remember that they are not words, your text should still make sense without them, so name them outside of the brackets if the reference is a subject or object.

Use simple words even if you have to reuse the same words over and over. You are not writing poetry, repetition is not a problem, changing which word you use for the same concept merely confuses readers. Be as direct as you can, and especially avoid filler words such as “it is widely known that” which can be removed entirely, or “in order to” which can be replaced by “to”. To decide whether individual words are complex or optional, ask yourself whether the sentence still works without them or with a simpler word, which is surprisingly often the case.

Do not try to be fancy, which is especially confusing for non-native readers and readers that do not share your cultural background in general. Do not use expressions in dead languages, such as “ceteris paribus”, aside from the few widely accepted ones such as “et al.”. Do not use unusual plurals such as “fora” or “data”, unless you also order many “pizze” when going out with your friends. Do not use grandiose qualifiers such as “there is no doubt” or “it is far from trivial”.

Proofreading

Everybody makes mistakes, so plan on proofreading your paper to minimize the odds these mistakes make it to the final version. This is especially important for inconsistencies between sections.

Send your draft to someone else, even if they are not in your field. The main kind of mistake you want to avoid is text that doesn’t make sense to the average reader, so feedback from a specialist is not sufficient. Tell people what kind of feedback you want, such as spotting typos vs discussing the overall structure, so you don’t waste their time. Remember that each person can only read your text for the first time once, after which they become less representative of your readers and reviewers.

You can get decent feedback from yourself at the sentence and paragraph level, if you use the following tricks. First, go do something else for at least a day and read your text again. Second, use text-to-speech software to read your entire paper in a boring voice, forcing you to focus on individual sentences. Third, read your paper paragraph by paragraph starting from the end, forcing you to focus on individual paragraphs.

Plagiarism

Plagiarism is unacceptable, thankfully there’s a really easy way to avoid it.

Never copy text from anywhere unless you immediately put it in quotes and reference its source. Plagiarism is not about a percentage of similarity, nor about the intent of the writer. It does not matter how much rewriting or even automated thesaurus-based replacement you do, copying text without quotes and attribution is plagiarism. This applies even to your own past work, which you should challenge yourself to write from scratch even better than last time.

Collaborating

It is unlikely that you are the sole author in your work, so keep good relationships with your coauthors and avoid unnecessary friction.

Compromise when you have to, better writing is not worth losing professional relationships over. This is especially true if you are a grad student or postdoc and the coauthor who disagrees is your advisor. Pick your battles wisely.

Standardize tooling across coauthors, any time you spend on tooling issues is wasted time. This is another common reason to compromise, especially if one author is unable to use a tool for technical reasons such as availability on the operating system they use. This also applies to rendering graphs and converting images for publication, since different tools can have different outputs and especially different bugs.

Acknowledgments

This guide was inspired by many sources I came across during my PhD, particularly Simon Peyton Jones’s “How to write a great research paper”. The four-sentence abstract structure is from John Wilkes. Larry McEnerney’s “The Craft of Writing Effectively” lecture is a great introduction to how academic writing differs from how you were writing in school. Stanford’s Writing in the Sciences online course is also good. Thanks to Clément Pit-Claudel for the tip about cutting initial sentences to make the intro punchier.